Decoding Chemical Behavior: Mastering Periodic Trends in Atomic Radius and Ionization Energy

Imagine the Periodic Table as a treasure map. It doesn’t just list elements. It shows how they act and react. Your spot on this map decides your size and how tightly you hold onto electrons. We call these patterns periodic trends. This article explores two key ones: atomic radius and ionization energy. We’ll break down why they change across rows and down columns. You’ll see the forces at play, like nuclear pull and electron shields. By the end, you’ll predict element behavior with ease.

Understanding Atomic Radius: The Size of the Atom

Defining Atomic Radius and Measurement Challenges

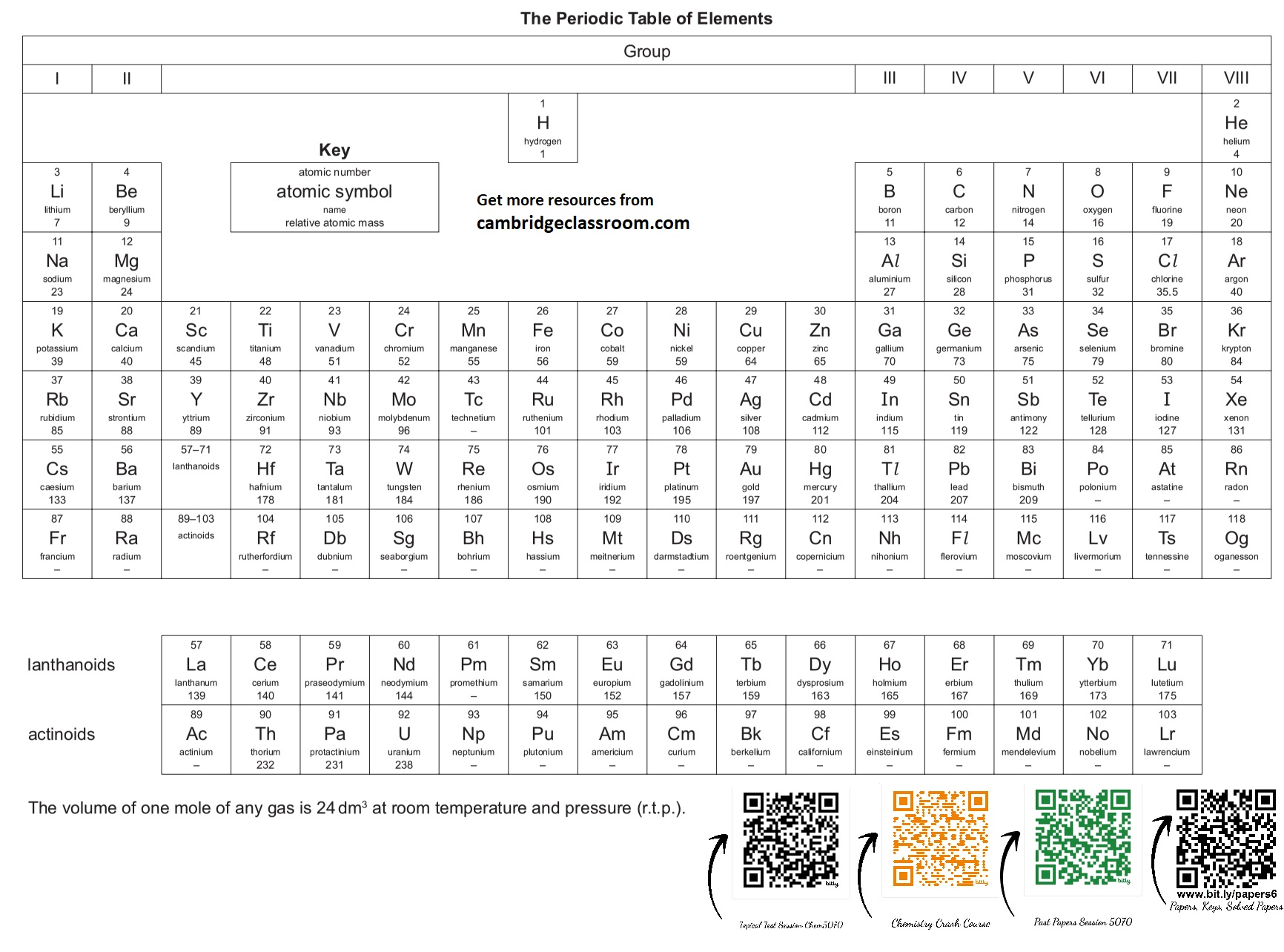

Atomic radius means the size of an atom. It’s half the distance between nuclei in two identical atoms bonded together. But atoms don’t have sharp edges. Scientists measure it in different ways. Covalent radius works for shared bonds in molecules. Metallic radius fits atoms in solid metals. Van der Waals radius applies to non-bonded atoms close together. These methods give close values, but not exact ones. Why? Atoms shift shape based on their company. This makes atomic radius a useful estimate, not a fixed number.

You might wonder how we pick the right measure. For carbon, the covalent radius is about 77 picometers. That’s tiny—smaller than a hair’s width. These definitions help us compare elements fairly. They reveal trends in the Periodic Table.

Periodic Trend Across a Period (Left to Right)

Atomic radius shrinks as you move left to right in a period. Take period 3: sodium starts big at 186 picometers. Chlorine ends smaller at 99 picometers. What’s the cause? The nucleus gains protons. Each proton boosts the nuclear charge. Electrons don’t get new shells here. So, the extra pull tugs electrons closer. We call this effective nuclear charge, or Z effective. It squeezes the electron cloud tight.

Picture it like kids on a playground. More “bossy” protons pull the electrons inward. No new levels mean less room to spread out. Alkali metals like lithium feel loose. Halogens like fluorine get cramped. This decrease affects how elements bond. Smaller atoms pack denser in compounds.

Exceptions pop up, but the rule holds strong. Across most periods, size drops steady. This trend links to reactivity too. We’ll connect that later.

Periodic Trend Down a Group (Top to Bottom)

Now go down a group. Atomic radius grows bigger. In group 1, lithium measures 152 picometers. Cesium reaches 265 picometers at the bottom. New electrons fill higher energy levels. These shells push outer electrons farther from the nucleus. Inner electrons shield the pull. This screening effect blocks some nuclear charge. Valence electrons feel less tug.

Think of layers in an onion. Each new shell adds bulk. Shielding weakens the core’s grip. That’s why potassium dwarfs sodium above it. Electron shielding drives this growth. It makes lower elements softer and more spread out.

This pattern repeats in every group. Metals expand down the table. It shapes their uses, from lightweight lithium batteries to heavy cesium clocks.

Ionization Energy (IE): The Fight to Keep Electrons

What is Ionization Energy? (IE)

Ionization energy is the energy needed to yank off an electron. It targets the outermost one from a lone gas atom. We measure it in kilojoules per mole. First ionization energy, IE1, removes the first electron. Second, IE2, takes the next. Each step gets harder. Why? The atom loses negative charge. The nucleus pulls harder on what’s left.

For sodium, IE1 is 496 kJ/mol. That’s the energy to strip its lone valence electron. Noble gases have high IE values. Their full shells resist change. Successive IEs skyrocket after valence electrons go. This concept helps explain why atoms form ions.

You can track IE trends just like radius. They tie together in neat ways.

Trend of Ionization Energy Across a Period

Ionization energy rises left to right in a period. Lithium’s IE1 is 520 kJ/mol. Neon tops at 2081 kJ/mol. Smaller radius means electrons hug the nucleus close. Higher nuclear charge clamps them tight. Valence electrons face more pull. It takes extra energy to break free.

Noble gases show the peak. Their filled p subshells stay stable. Removing an electron disrupts that peace. Halogens like fluorine have high IE too, but not as high as neon. They crave one more electron instead.

This climb predicts metal to nonmetal shift. Left-side elements lose electrons easy. Right-side ones hold on fierce. Real labs confirm this pattern every time.

Trend of Ionization Energy Down a Group

Down a group, ionization energy falls. In group 1, lithium’s IE1 hits 520 kJ/mol. Cesium drops to 376 kJ/mol. Valence electrons sit farther out. Shielding from inner shells softens the nuclear pull. Bigger distance means weaker grip. Less energy frees the electron.

Group 17 follows suit. Fluorine’s IE1 is 1681 kJ/mol. Iodine eases to 1008 kJ/mol. The drop averages 200-500 kJ/mol per group. This makes bottom elements more reactive in losing or gaining electrons.

Francium, at the bottom, reacts wild. Its low IE sparks quick bonds. These trends guide how we handle elements safely.

Anomalies and Exceptions in Periodic Trends

Deviations in Atomic Radius Trends

Atomic radius trends aren’t perfect. Look at group 13 versus 14. Aluminum in group 13 has a radius of 143 picometers. Silicon in 14 shrinks less than expected at 118 picometers. P orbitals in group 13 penetrate closer to the nucleus. This pulls size down more.

Then there’s lanthanide contraction. In period 6, sizes dip sharp after lanthanum. Hafnium matches zirconium’s size from period 5. F electrons shield poorly. Protons add pull without much block. This contraction affects heavy metal properties.

These glitches remind us electrons behave quirky. Still, main trends hold for predictions. Lanthanide contraction explains rare earth tech challenges.

Explaining Irregularities in Ionization Energy

Ionization energy has dips too. In a period, group 2 beats group 13 slightly. Beryllium’s IE1 is 899 kJ/mol. Boron’s is 801 kJ/mol. Full s subshell in group 2 stays stable. Removing a p electron from boron takes less fight.

Another drop hits group 15 over 16. Nitrogen’s IE1 is 1402 kJ/mol. Oxygen’s falls to 1314 kJ/mol. Half-filled p subshell in nitrogen resists change. Paired electrons in oxygen repel easier. One leaves with less energy.

These exceptions stem from subshell stability. They fine-tune the overall rise. Chemists watch them in detailed studies. Such patterns sharpen our Periodic Table skills.

Connecting Atomic Radius and Ionization Energy

The Inverse Relationship Explained

Atomic radius and ionization energy link inverse. Big atoms have low IE. Small ones demand high IE. Valence electrons in large atoms wander far. Weak pull lets them escape cheap. Tiny atoms keep electrons locked near the nucleus.

Dmitri Mendeleev noted this in his table days. He saw size as key to reactivity. Modern chemists agree. Effective nuclear charge rules both. As radius shrinks, IE climbs. This pair drives Periodic Table logic.

You see it in data. Lithium’s big size pairs with 520 kJ/mol IE. Fluorine’s small frame hits 1681 kJ/mol. The bond is clear and strong.

Implications for Chemical Reactivity

These trends forecast how elements react. Low IE in group 1 means easy electron loss. Sodium forms Na+ ions quick. It reacts with water in bursts. High IE in group 17 makes halogens grab electrons. Chlorine bonds fierce to metals.

Noble gases sit inert with top IE and small size. Helium ignores most reactions. Here’s a quick chart:

- Alkali Metals (Group 1): Large radius, low IE. Highly reactive, lose one electron easy. Example: Potassium in fireworks.

- Halogens (Group 17): Small radius, high IE. Reactive nonmetals, gain one electron. Example: Iodine in disinfectants.

This inverse duo shapes bonds and compounds. Metals donate. Nonmetals accept. Understanding it unlocks chemistry’s basics.

Conclusion: Predicting Chemical Destiny

Periodic trends boil down to two forces. Effective nuclear charge squeezes atoms across periods. Principal energy levels and shielding expand them down groups. Atomic radius shrinks left to right, grows top to bottom. Ionization energy does the opposite.

The inverse tie stands firm. Bigger size means easier electron loss. This framework predicts reactions for most elements. From sodium’s fizz to neon’s calm, it all fits.

Master these, and the Periodic Table becomes your tool. Test it with a simple experiment at home, like observing metal reactivity. Dive deeper into trends for better science grasp. Your chemical world just got clearer.